Promising Prospects for Equipment Finance in 2026

The equipment finance sector is poised for a brighter future in 2026, driven by government policies and investments in data centers and artificial intelligence, offering new avenues for financiers.

Economic Growth and Industry Expansion

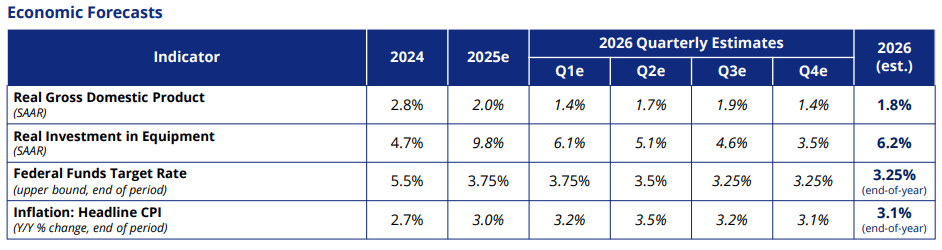

As the U.S. economy heads towards 2026, it shows resilience with a projected GDP growth of 1.8% and a 6.2% rise in equipment and software investments, according to the latest report from the Equipment Leasing and Finance Foundation. The demand for equipment, coupled with AI-driven capital expenditures and robust equity markets, is expected to fuel industry growth.

Systemic Changes and Opportunities

Michael Sharov, a partner at Oliver Wyman, highlights that the equipment industry is undergoing systemic changes rather than a typical cyclical downturn. Factors such as evolving distribution channels, customer segmentation, labor shortages, and digital realignment are reshaping the landscape, creating opportunities for dealers, lenders, and OEMs.

“Systemic change is inevitable, but the industries will remain intact.” – Michael Sharov, Oliver Wyman

Despite challenges, the industry serves essential sectors like food and infrastructure, ensuring confidence in recovery. Lenders face challenges related to asset transparency, service capacity, and the importance of used equipment, even as the long-term outlook remains strong.

Strategic Mergers and Acquisitions

In the transportation sector, mergers and acquisitions are expected to enable stronger companies to acquire clients as industry capacity shifts, according to Anthony Sasso, head of TD Equipment Finance. Financially stable companies are already seizing opportunities to expand their client base.

Growth Drivers for 2026

The equipment finance industry is set for growth alongside the U.S. economy’s recovery from economic uncertainties, says Cedric Chehab, chief economist at BMI. Factors such as fiscal stimulus, bonus depreciation, anticipated Federal Reserve rate cuts, and continued AI and data center investments are key growth drivers.

“AI and its integration with robotics could significantly boost productivity,” Chehab notes. “The U.S. is aggressively investing in cutting-edge technology, accelerating development and competition.”

Impact of the One Big, Beautiful Bill Act

The One Big, Beautiful Bill Act, signed by President Trump, is expected to spur equipment investment by making bonus depreciation permanent, allowing firms to fully expense capital equipment. This, along with other tax incentives and lower borrowing rates, should support investment growth and sustain the CapEx cycle.

However, TD’s Sasso cautions that while increased deductions and financing can enhance liquidity, they may not suffice to drive new equipment purchases in sectors like trucking without additional factors.

Data Centers and Construction Growth

Investment in data centers and technology is projected to continue, with financing for U.S. data centers expected to reach $60 billion in 2025. Despite this, traditional CapEx categories like transportation equipment and commercial construction face challenges.

In the construction sector, sentiment remains cautious, with many firms in the Minneapolis Federal Reserve region expressing pessimism about growth prospects.

Challenges and Cautious Optimism

According to Oliver Wyman’s report, the industrials market’s current state is rated at 5.7 out of 10, down from 8 last year. Key indicators like farm receipts and construction activity will be crucial in assessing demand across agriculture and construction sectors.

“There is cautious optimism, but the sentiment hasn’t improved significantly.” – Nate Savona, Oliver Wyman

While the outlook for 2026 is optimistic, risks such as a weakening labor market, unexpected inflation, limited Fed easing, potential AI bubble, trade tensions, and political uncertainty remain.

Despite these challenges, there is hope for a rebound in the trucking industry, which could signal broader economic recovery, according to TD’s Sasso. “We may be at a low point, but there’s optimism for 2026, which could benefit all businesses.”

Explore our exclusive industry data here.